Active vs. Passive Stretching… What’s the Difference?

Jul 07, 2021

Written by Dr. Ryan Peebles, DPT

I’ll start by emphasizing that there’s a BIG difference… and you should know which one you’re doing.

The motivation to stretch may vary from person to person. Your goal could be to increase flexibility, to warm up for an activity, simply to feel better, or because you’ve heard “you should stretch” your entire life.

Whatever your goal is, if you’re like me, you probably prefer the benefit of your efforts to be long-term rather than short-term. And that’s precisely where the difference lies: Active stretching has significantly longer lasting benefits than passive stretching.

In other words, if you want the increased flexibility from your stretching session to last beyond your next meal, you should be actively stretching. Now the big question:

What is Active Stretching?

(And how does it differ from passive stretching)

Both activities center around physically lengthening the muscles. The difference is in how that is happening.

If you do a basic Google search, you’ll learn that active stretching uses your own muscle force to create the stretch, while passive stretching uses an external force such as gravity, a strap, or some other prop.

In other words, with active stretching you’re actively holding your stretch with other muscles - usually the opposite muscle group. An example would be holding your straight leg up in the air to stretch your hamstrings without the use of a strap; it takes effort from your hip flexors to hold your leg up.

This is all true, but once again Google is not showing the full picture… there is something else that must happen if you want the benefits to carry over to the next day. Here it is:

The muscle you're stretching MUST be "active" while in the stretch.

Said differently, if your goal is to actively stretch your hamstrings, then you must actively engage, or contract your hamstrings at some point during the stretch. One technique commonly used in physical therapy is called PNF stretching, where one alternates between periods of contracting and relaxing a stretched muscle. But there are many other ways to stretch actively.

For example, yoga. When performing a standing pose such as Warrior, all your muscles - even the stretched ones - are actively involved in holding this position. It’s called co-contraction and is what keeps you stable. Without it, you would lose your balance.

In the previous example of holding your straight leg up to stretch your hamstrings, the hip flexors are actively involved, but the hamstrings could potentially be passive the entire time. There is nothing about that stretch requiring your hamstrings to be actively involved or contract.

Meaning, the benefits would not last any longer than they would from a completely passive stretch (eg. with a strap). I’ll get into the science of why in a minute, but first, let’s turn this example into a truly “active” stretch.

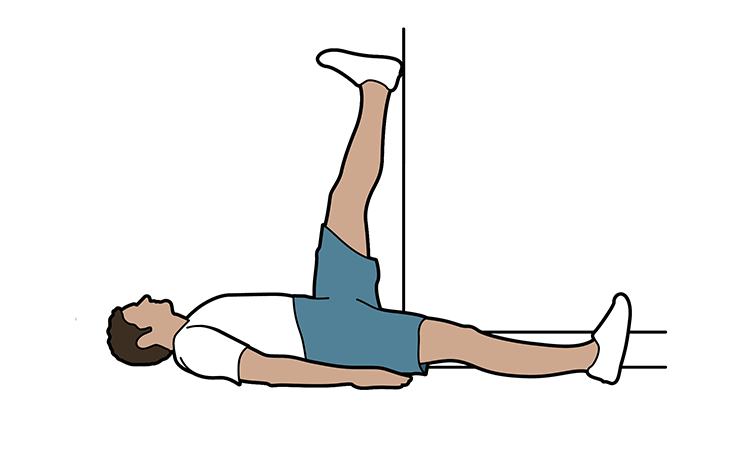

Let’s say you’re performing this stretch lying on the ground in a doorway. You lift your straight leg up to stretch your hamstrings, and once in the fully lengthened position, you put the back of your leg up against the wall of the doorway. Now, you have some resistance to push against.

If you push into the wall with the back of your leg/heel, you are actively engaging your hamstrings while in the stretched position, turning this into an “active” hamstring stretch.

In the simplest terms, active stretching takes effort from the muscle being stretched, while passive stretching allows that muscle to stay relaxed the entire time. Now, let’s briefly get into the science of why this matters.

Muscle fibers have elasticity, like the waist band of a new pair of underwear. You can stretch them, but they will return to their original length unless you hold them stretched for a very long time. This is the capacity of passive stretching.

For long term changes in a muscle’s length, we need to get beyond elasticity. We need to train the muscle to want to stay in the newly lengthened position. We need to increase the resting length of a muscle, which is a function of the nervous system.

In other words, to make a stretch last, we need to involve the nervous system in the stretch. By contracting the muscle in the stretched position, we are training the neuromuscular (nerve-muscle) system to function in this new, vulnerable position. We’re saying,

"I can operate here without tearing or injuring myself."

The nervous system needs to know that it can operate safely, or it will protect itself by returning back to its comfort zone. In a sense, engaging a muscle in a new length is like telling the nervous system,

"It’s safe to stay here."

It’s kind of a metaphor for life. In order to expand ourselves, we need to stretch beyond our normal limits AND learn to operate safely, or else we return back to our previous way of being.

So in a nutshell, learn to use (activate/engage/contract) your muscles in the stretched position. Otherwise you're not actively stretching the muscle, and the stretch won’t last.

To gain the range, train the range.

Questions?